Case study – Hybrid polymer–lipid nanoparticles

Optimising hybrid polymer–lipid nanoparticles for a novel malaria nanotherapy using SPARTA®

How single-particle analysis helped confirm hybridisation and identify the strongest candidates for development

Researchers at Imperial College London are developing an innovative hybrid polymer–lipid nanoparticle therapy for malaria. For the therapy to be effective, both the polymer and lipid must be integrated within the same individual particles. Unlike traditional bulk methods that provide only averaged measurements, SPARTA® provided detailed single-particle compositional analysis, enabling the team to confirm polymer–lipid co-assembly, compare differences in heterogeneity, and optimise their formulations.

The challenge

The novel malaria therapy uses nanoparticles that combine a targeting polymer, engineered to mimic the receptors malaria parasites use to attach to host cells, with lipids that form the stable structure. These hybrid nanoparticles bind to the parasite and prevent it from invading red blood cells and causing infection.

The team began by characterising their nanoparticles using standard bulk analytical methods, including:

• Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): to measure particle size and distribution

• Zeta potential analysis: to assess surface charge and stability

• Small-angle scattering: to examine overall morphology and internal structure

These techniques verified the expected physical properties, but they only provide bulk-average measurements. As a result, any particle-to-particle differences were masked, and none of these methods could reveal the chemical composition of individual nanoparticles.

To gain single-particle resolution, the researchers also used cryo-TEM, which allowed them to visualise particle shape, layering and general morphology. However, cryo-TEM still could not determine what each particle was made of or whether the polymer and lipid were co-localised within the same nanoparticle. This is essential if the therapy is to work as intended.

The solution

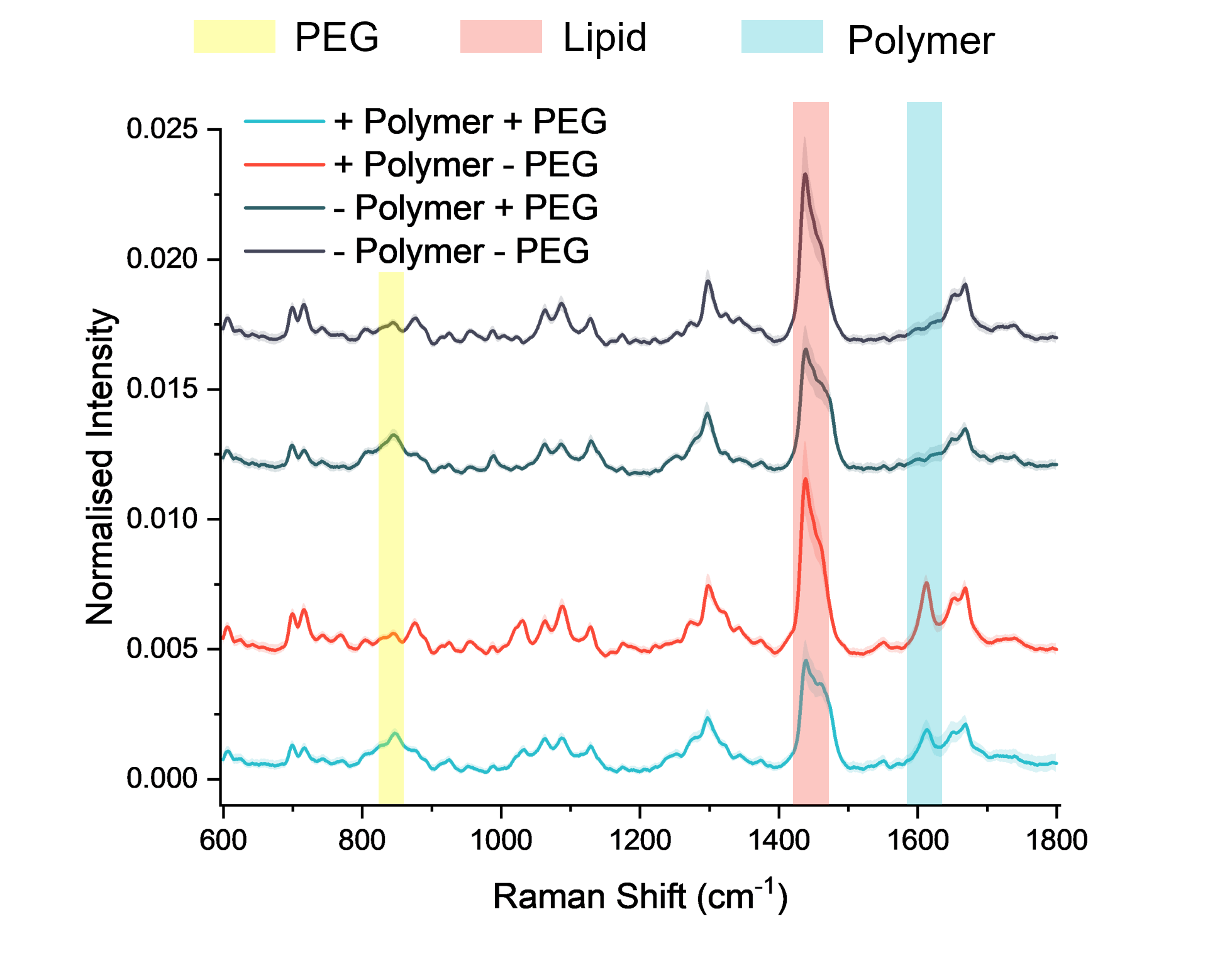

To overcome the limitations of bulk analytical techniques, the Imperial researchers turned to SPARTA® (Single Particle Automated Raman Trapping Analysis), a next-generation platform that combines optical trapping with Raman spectroscopy to generate non-destructive, label-free chemical fingerprints of individual nanoparticles.

Using SPARTA®, the researchers were able to:

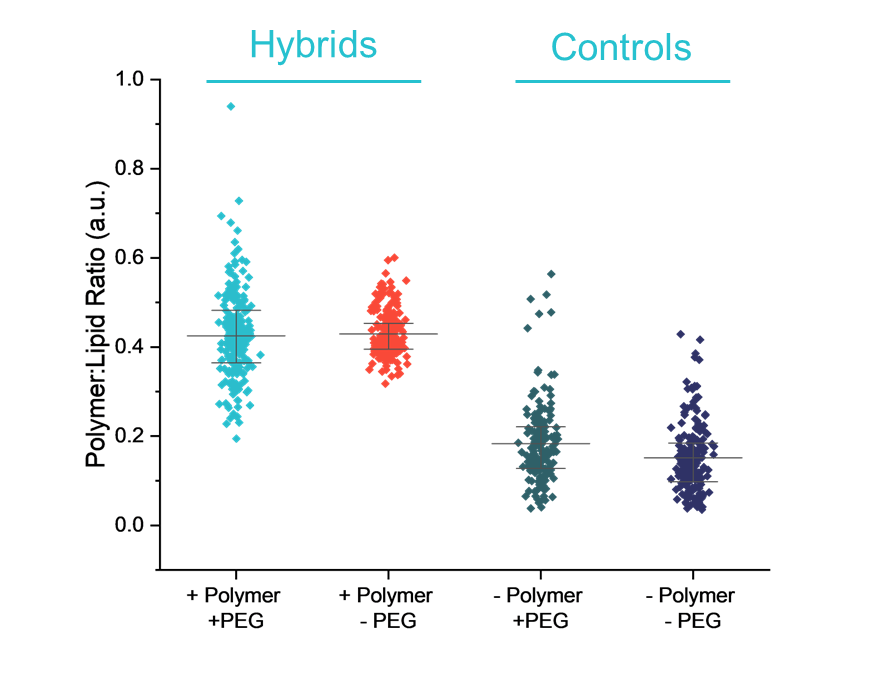

- Assess particle-to-particle heterogeneity: Single-particle data uncovered variability in composition that bulk measurements couldn’t, allowing the researchers to identify which formulations were uniform and which showed high heterogeneity. Choosing formulations with low heterogeneity is important because nanoparticles with consistent polymer loading are more likely to behave predictably and work more effectively, whereas highly heterogeneous formulations contain a mix of well-loaded and poorly loaded particles that can reduce overall performance.

- Understand the impact of PEG-lipids: PEG-lipids were added to improve stability and circulation time, but SPARTA® revealed that they also increased particle-to-particle heterogeneity. This insight helped the team understand how PEGylation influences the overall consistency of the formulation and make more informed decisions about balancing stability with heterogeneity.

Outcome

Having confirmed that the polymer and lipid were co-localised within the same nanoparticles, the researchers were then able to optimise their formulation using SPARTA®.

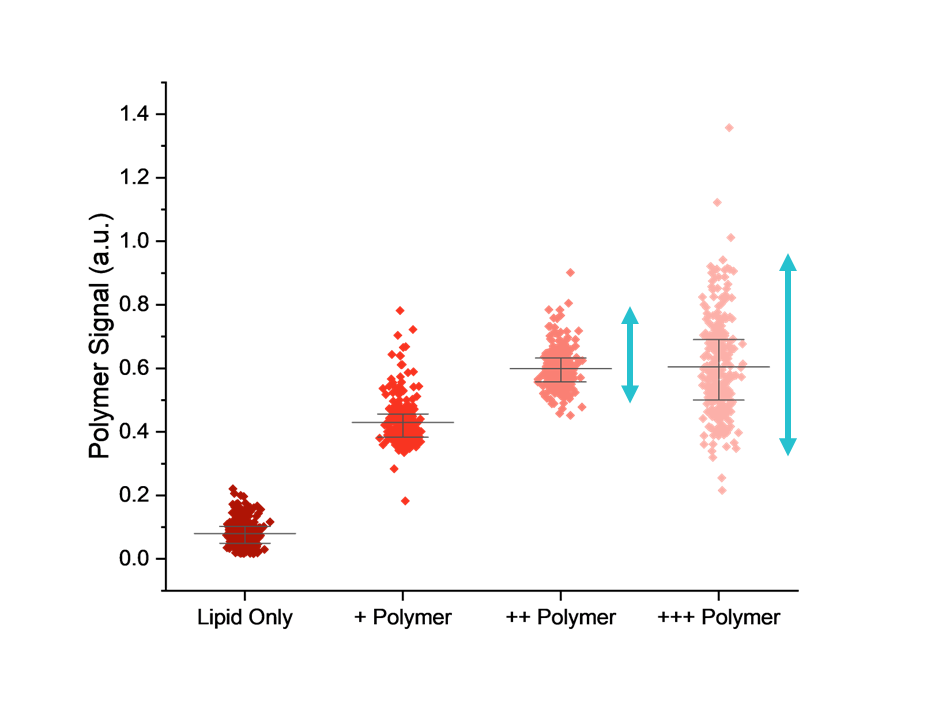

Adjusting the polymer-to-lipid ratio and observing how this affected nanoparticle composition showed that increasing the amount of polymer initially boosted the average amount incorporated into each particle. However, beyond a certain point, additional polymer no longer improved loading and instead increased particle-to-particle heterogeneity, leading to a less consistent population.

This allowed the team to identify a sweet spot where polymer input maximised incorporation while keeping heterogeneity low, enabling them to focus their resources on the most promising candidates for progression into biological testing.

References

- Najer, A. et al. (2022) ‘Potent virustatic Polymer–Lipid nanomimics block viral entry and inhibit malaria parasites in vivo,’ ACS Central Science, 8(9), pp. 1238–1257. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.1c01368.

- Najer, A. et al. (2024) ‘Enhanced antimalarial and antisequestration activity of Methoxybenzenesulfonate-Modified biopolymers and nanoparticles for tackling severe malaria,’ ACS Infectious Diseases, 10(2), pp. 732–745. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.3c00564.